No evidence for neuroscience bias in adult or juvenile cases:A pre-registered mock juror study

Image credit: Fig1

Image credit: Fig1

摘要

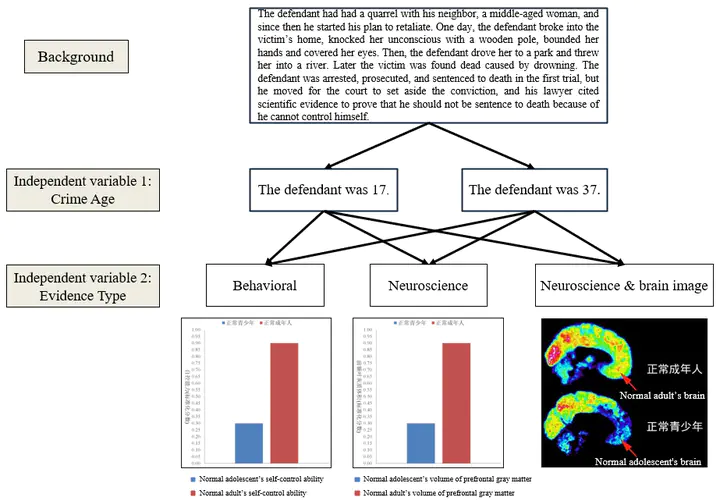

In last two decades, developmental neuroscience results had been cited in high-profile legal cases in the United States and other countries. However, it’s unknown whether neuroscience evidence bring bias because of its over-persuasiveness for people without training in neuroscience. Previous studies suggested that neuroscience results were over-persuasive, this effect was termed as “neuroscience bias,” but the evidence was not conclusive because of failed replication attempts. Moreover, few studies directly examined the effect developmental neuroscience in juvenile cases. To address this issue, we conducted two mock jury studies with a three (evidence type:behavioral evidence, neuroscience evidence without brain images, and neuroscience evidence with brain images) by two (offenders’ age:juvenile vs. adult) between-subject design. In a pilot study (n = 94) and pre-registered study (n = 324), participants first read a vignette, which described an offender murdered a victim and his lawyer introduced scientific evidence when defending for the offender. Participants were required to make a series of judgments, including death penalty and criminal responsibility of defendant. The results revealed a main effect for offenders’ age, but no effect for evidence type or interaction between evidence type and offenders’ age. An exploratory conditional random forest analysis again revealed that evidence type was not important in predicting participants’ judgment. Instead, other self-reported variables are more important, such as the “just deserts” view of criminal punishment and the perceived possibility the offender would re-enter society. These results suggest that, in the severe criminal cases, the neuroscientific evidence is not more persuasive than behavioral evidence, regardless the neuroscientific results are from adults or juveniles.